Advent means “coming." It is the season we mark how God came near to us in the birth of Jesus, and it is also a time we should look for all the ways God still comes to us in the places we least expect. The great theme of these stories is that God is with us— God is with all of us, and in fact this story goes out of its way to show that God is most present with the people and places we are tempted to think are separate from God.

Matthew’s version of Jesus’ birth story starts off with a genealogy—Don’t worry, I’m not including this laborious list of names to challenge your love for the Bible. I always skip the lists, myself! I wanted us to start Jesus’s story here, because this genealogy is meant to help us understand who this story is for.

Scholars tell us that Matthew is clearly not very interested in historical accuracy with this list of names; this is a symbolic and theological genealogy.1 It is a metaphor that Matthew uses to tell us something about God— that God is with us in every messy part of our story.

Here it is; and feel free to pick back up with me on the other side:

Matthew 1:1-17

The Genealogy of Jesus the Messiah

1 An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham.

2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, 3 and Judah the father of Perez and Zerah by Tamar, and Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezron the father of Aram, 4 and Aram the father of Aminadab, and Aminadab the father of Nahshon, and Nahshon the father of Salmon, 5 and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of Jesse, 6 and Jesse the father of King David.

And David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah, 7 and Solomon the father of Rehoboam, and Rehoboam the father of Abijah, and Abijah the father of Asaph, 8 and Asaph the father of Jehoshaphat, and Jehoshaphat the father of Joram, and Joram the father of Uzziah, 9 and Uzziah the father of Jotham, and Jotham the father of Ahaz, and Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, 10 and Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, and Manasseh the father of Amos, and Amos the father of Josiah, 11 and Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon.

12 And after the deportation to Babylon: Jechoniah was the father of Salathiel, and Salathiel the father of Zerubbabel, 13 and Zerubbabel the father of Abiud, and Abiud the father of Eliakim, and Eliakim the father of Azor, 14 and Azor the father of Zadok, and Zadok the father of Achim, and Achim the father of Eliud, 15 and Eliud the father of Eleazar, and Eleazar the father of Matthan, and Matthan the father of Jacob, 16 and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah.

17 So all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations; and from David to the deportation to Babylon, fourteen generations; and from the deportation to Babylon to the Messiah, fourteen generations.

Honestly if you read all of that i’m going to judge you and call you a legalist! But even if you took only a brief glance at the text as you scrolled down, you may have noticed something odd about this family history: This list is very dude-centric. It’s all boys, boys, boys. Ancient genealogies didn’t have women’s names in them; the family history went from daddy to daddy, as if people with penises were capable of creating more people with penises, with no other equipment involved or necessary! Welcome to the patriarchy, babes. However, Matthew breaks this form by including four women along the way and culminating with “Mary, of whom Jesus was born,” which is Matthew’s way of reminding us that Joseph wasn’t even Jesus’s father. I’m not suggesting that Matthew was a feminist, but by the way he is framing Jesus’s history, we can already see that Jesus’s story is going to challenge who society says matters. In the story of Jesus, we learn that everyone matters to God.

Not only was it unique for Matthew to mention women in his genealogy, but every woman Matthew mentions has some involvement with sexual scandal. These would have been considered, in the immortal words of our misogynist-elect Donald Trump, nasty women. Matthew does not hide the messy bits of Jesus’s story, he drags them out of the closet to highlight the radical inclusion at the heart of Christian spirituality.

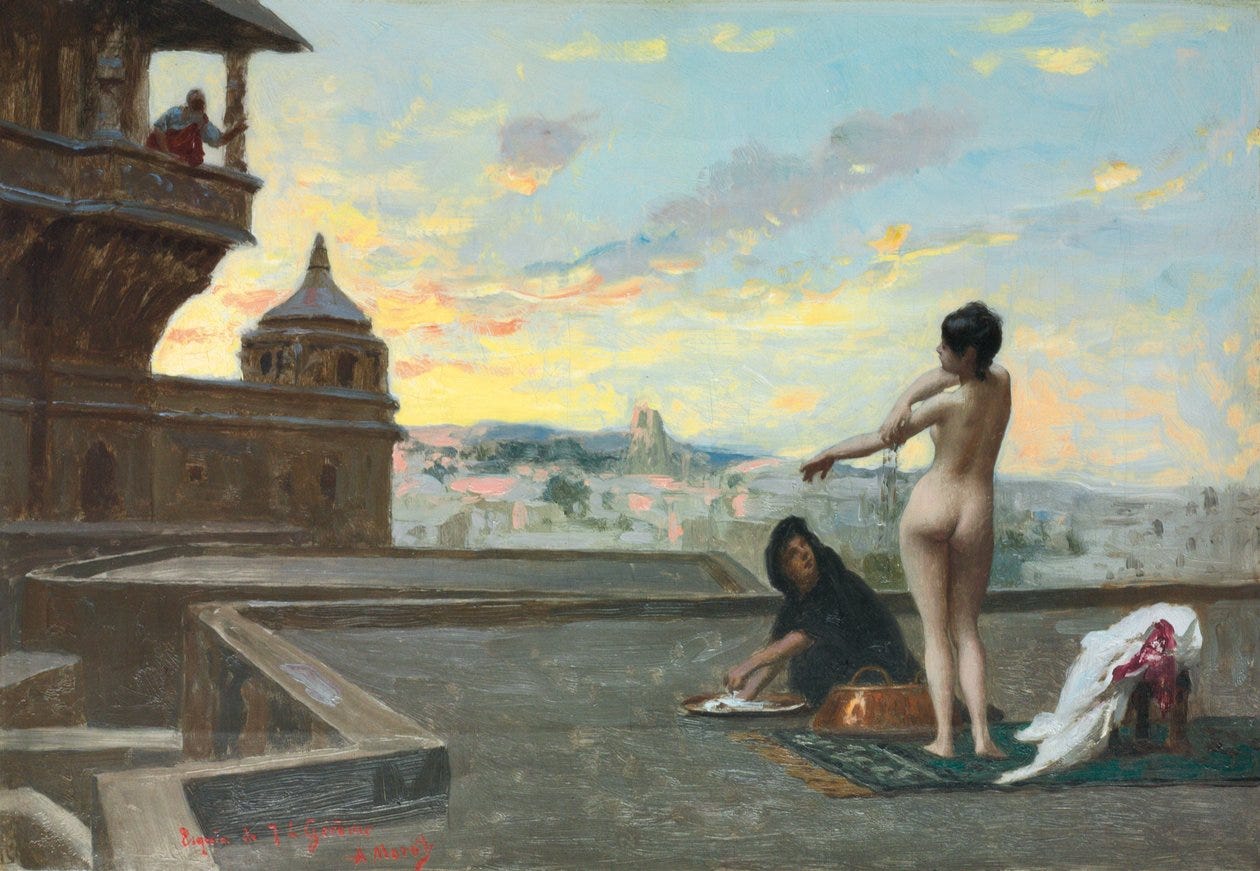

The first is the salacious story of Judah and Tamar. Tamar was a foreigner– a Canaanite– and she married Judah’s son. After her husband died, Tamar disguised herself as a veiled prostitute, and slept with her Father-in-law to gain an heir. When Judah saw that Tamar was pregnant, he tried to have her killed for the sin of prostitution… until she revealed that Judah himself had been her client! Tamar the prostitute is vindicated over Judah the patriarch.

The second is Rahab. She was also a Canaanite. In fact, all 4 women added to Matthew’s list are outsiders; none are Israelites. From the beginning of Jesus’s story, we see that grace is especially those we consider outsiders, because there are no outsiders to God. Rahab was also a prostitute, and as much as I’ve searched, I haven’t found the Bible verse where she was told she needed to repent for her profession. Instead, she is given an honored place in the lineage of the Messiah.

Third is Ruth. Sweet, pure Ruth, whose reputation for timidity is severely unfounded. I mean this as a compliment! Ruth is a baddie. Christian women are often given advice like, they “should never make the first move,” because “a man is the initiator, and he is meant to pursue.” Well somebody should have told Ruth. In today’s episode of “they didn’t tell you this in Sunday School,” you may find it interesting to know that when Ruth snuck into Boaz’s tent and “uncovered his feet” (Ruth 3:4), this is a well known Hebrew euphemism for uncovering his genitals. Ruth, our godly heroine, most likely had (Biblically celebrated and God-sanctioned) premarital sexual intimacy. Gasp! Although many evangelical churches would call this Jezebel behavior, Matthew would like us to remember the way she audaciously took things into her own hands, and thus became an ancestor to the Christ.

The fourth woman, Bathsheba, goes unnamed. We are told “David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah.” Matthew phrases it this way to highlight a very inconvenient fact about one of Israel’s greatest heroes– David murdered Uriah after raping his foreign wife Bathsheba in order to claim her as his own. None of these unseemly details are necessary for a genealogy. Matthew could have stuck to the “Father of” formula and left the women out of it! But he wants us to know that Jesus’s story is for women and foreigners. This is a story for the victims of powerful men. It is a story for the abused and downtrodden. In this story, the voiceless will get a voice. That’s what the way of Jesus is all about.

Those deemed "unworthy" by societal and religious standards are the people who God chooses. Barbara Brown Taylor says that this radical inclusion “is a challenge to every human system that depends on the distinction between who is in and who is out.” God cannot be contained by our church, our tribe, our denomination, or even our religion.

Many conservative Christians think of their exclusion as faithfulness. They may pride themselves that when they draw hard lines on excluding sexual minorities, they are “taking a hard stand for truth” even though many find their bigotry offensive. But as we see again and again, the true offense of the Gospel is always who is included, not who is excluded. We are being introduced to a God who vindicates the very people that our religious standards condemn.

God doesn’t seem to care much for our purity standards that whitewash Ruth’s story or expect Rahab to repent of sex work before being used by God. God is likely to be most at work in the very areas of our lives that don’t seem to fit with social norms, hierarchies, or religiosity. God is at work in our queerness and in our nonconformity. God is at work in our truest selves, whatever and whoever we are. This is a God for everybody.

You might still ask, why would Matthew (and also Luke) invent genealogies for Jesus? These metaphorical genealogies do not prove that Jesus is the divine Son of God, as much as they give us the meaning of Jesus’ divinity. Scholars think that one of the reasons they did this is to create a contrast with the another person in the ancient world who was believed to be the “divine Son of God.” Caesar Augustus, the Emperor of Rome. The Caesars claimed descent from the gods of Roman legend to affirm their authority and power.

In contrast, Matthew gives us a countergenealogy, a radical reimagining of what it means to have divine blood, where divine lineage comes not from gods of empire, but from prostitutes and foreigners. The divine is present within the messy, painful, lives of the oppressed.

As we begin this journey through the story of Jesus’ birth, may we remember that we do not have to clean up our stories in order to welcome God. This story turns our systems of exclusion upside-down and brings those who had been kept out right to the center.

God is not offended by our humanness; God is born into it.

Take a moment to breathe and consider your own story. Imagine the parts that feel most disqualifying or embarrassing. Imagine the divine choosing you in love for those exact moments in your story as you pray this breath prayer:

Inhale: God is in my story. (4 seconds)

-HOLD- (4 seconds)

Exhale: Especially in the messy details. (4 seconds)

Inhale: Just as I am (4 seconds)

-HOLD- (4 seconds)

Exhale: God welcomes me. (4 seconds)

For more information on how the genealogies are symbolic and not historical, check out The First Christmas by the Biblical scholars Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan

Really, really appreciate this... Christ is not (only) born of virgins. ;) hm...

Thank you